Prison Life

Shin Dong-hyuk was born in and lived his whole life in a North Korean prison camp, until his escape. Interviewed at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C, he recalled his own captivity. “The misery suffered by the Jewish victims of the Nazi Holocaust is so similar to what I saw in North Korean prison camps.”

[One difference: North Korea’s concentration camps have now existed more than 12 times longer than the Nazi camps, and twice as long as the Soviet gulag.]

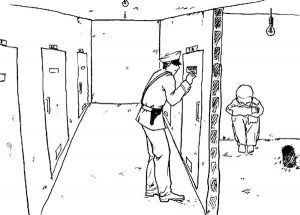

Shin’s frame has been permanently shaped by Camp 14. His shoulders are slightly hunched from heavy labor; skin on his back and rear is scarred from torture by fire in an underground prison; over his pubis sits a scar from the steel hook that was used to hold him over a charcoal fire as his skin bubbled; both of his shins are disfigured from the electrified fence, and his right middle finger is cut off at the first knuckle — punishment he received for dropping a sewing machine at one of the camp’s factories.

Families at Camp 14 get just two hours daily of electricity — from 4 a.m. to 5 a.m. and from 10 p.m. to 11 p.m. There are no beds, tables, chairs or running water. They use a communal privy, the waste from which is used as fertilizer for the camp farm. Almost anything at Camp 14 is viewed as edible. Shin and his fellow prisoners ate frogs, snakes, insects, rats —anything. In the winter, when food is scarce, prisoners try to abate hunger pangs by not defecating, regurgitating and re-eating food — nothing is off limits, but none of it changes the fact of starvation. Read more

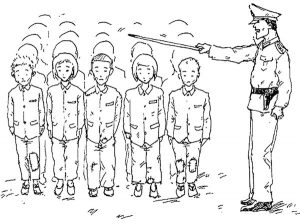

Shin Dong-hyuk had committed no sin, except by North Korean standards. Shin was there because he committed the crime of being the son of his father. He was born, in November 1982, at a forced labor camp for “political prisoners.” Unlike Jewish families in Europe who’d had lives before the Holocaust, Shin knew only Camp 14. He was, by his own account, not fully human. Shin had no concept of love, compassion or morality. His mother was not his guardian — she was competition for food. Read more

Shin Dong-hyuk had committed no sin, except by North Korean standards. Shin was there because he committed the crime of being the son of his father. He was born, in November 1982, at a forced labor camp for “political prisoners.” Unlike Jewish families in Europe who’d had lives before the Holocaust, Shin knew only Camp 14. He was, by his own account, not fully human. Shin had no concept of love, compassion or morality. His mother was not his guardian — she was competition for food. Read more

As a 13-year-old in a North Korean prison camp, Shin Dong-hyuk overheard his mother and brother speaking. One word made him perk up — escape. Knowing the rule, “Any witness to an attempted escape who fails to report it will be shot immediately,” Shin’s “camp-bred instincts took over,” as journalist Blaine Harden writes in “Escape From Camp 14.” Running out of the house and finding the school’s night guard, Shin did exactly what he had been raised to do — he ratted on his own mother and brother, explaining what he had overheard. Read more

Like its Nazi counterpart, the North Korean government sometimes uses prisoners as lab rats to test the potency of certain chemicals. Shin Dong-hyuk remembers when guards gave 15 inmates chemical solutions to rub on themselves. Shortly thereafter, they developed boils on their skin. As Harden wrote, “Shin saw a truck arrive at the factory and watched as the ailing prisoners were loaded into it. He never saw them again.”

Like its Nazi counterpart, the North Korean government sometimes uses prisoners as lab rats to test the potency of certain chemicals. Shin Dong-hyuk remembers when guards gave 15 inmates chemical solutions to rub on themselves. Shortly thereafter, they developed boils on their skin. As Harden wrote, “Shin saw a truck arrive at the factory and watched as the ailing prisoners were loaded into it. He never saw them again.”

According to The Guardian newspaper, prisoners and guards from Camp 22 in Hamgyong “described watching entire families being put in glass chambers and gassed.” An official document smuggled out by a defector said that 39-year-old Lin Hun-Nwa was transferred from Camp 22 “for the purpose of human experimentation of liquid gas for chemical weapons.” Read more

On the frigid afternoon of Jan. 2, 2005, something happened at the camp that had never happened before — someone escaped: Shin Dong-hyuk successfully crawled over his friend’s lifeless body, which shielded him for the most part from the deadly voltage pulsing through the barbed-wire fences. Read more … Over the next month he made his way 370 miles north, to the Chinese border, to freedom. Read more

[The above consists of excerpts from a Jewish Journal article authored by Jared Sichel]